November Curator’s Corner

Facts Uncover Legend of Lost Frémont Cannon

by Brett Fisher

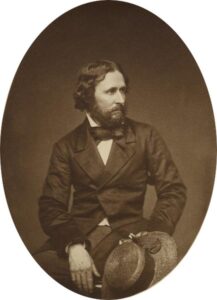

Each November, UNR and UNLV football teams play for the right to host the famed Frémont Cannon and paint its carriage in their school colors. As prized as this trophy is to players and fans of either program, though, it’s a far cry from the real McCoy. The real Frémont Cannon is a fabled archaeological treasure with a legend reaching farther back in time than Nevada’s storied intrastate football rivalry.

Each November, UNR and UNLV football teams play for the right to host the famed Frémont Cannon and paint its carriage in their school colors. As prized as this trophy is to players and fans of either program, though, it’s a far cry from the real McCoy. The real Frémont Cannon is a fabled archaeological treasure with a legend reaching farther back in time than Nevada’s storied intrastate football rivalry.

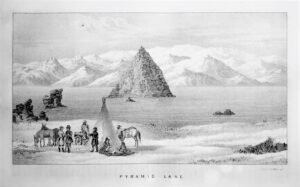

The U.S. Model of the 1835 12-pound Mountain Howitzer that Lt. John C. Frémont brought with him on his Second Expedition of 1843 was abandoned along the way and had been lost for years. Though much has happened since then, questions still surround the history behind Frémont’s Mountain Howitzer cannon. Chief among them is whether the expedition’s artillery piece had actually been found, or if it’s still a lost relic.

The Nevada State Museum has a mountain howitzer barrel in its collection consistent with the model taken by Frémont on his Second Expedition. This magnificently preserved artifact is known as the Captain A.W. Pray Cannon, which was donated by the Bliss family to the Nevada State Museum in 1941. With a 223-pound bronze tube (barrel) cast in 1836 by Cyrus Alger & Company out of Boston, Massachusetts, the Pray Cannon is compact, easy to disassemble for transport, and designed for portability. Facts about how the artillery piece came into Captain Pray’s possession, though, remain sketchy.

As one story goes, the Museum’s cannon was found near the Walker River and brought to Virginia City, where Frémont himself later saw it on a visit to the Comstock and proclaimed it to be his cannon. Virginia City journalist Dan DeQuille (William Wright) claimed to have discovered the howitzer in the Walker River area in 1859. A party was later organized to recover and deliver the abandoned artillery piece to Virginia City, where Captain Pray supposedly paid $200 for it in 1861. Pray then used the cannon for salutary purposes in Virginia City, Glenbrook, and Tahoe City.

Another account suggests Frémont recovered a U.S. Army artillery piece that had been captured by Mexican forces during the Battle of San Pasqual in Alta (upper) California, in 1846. The cannon was then transported to the Presidio in San Francisco and transferred to Fort Churchill during the Pyramid Lake War in 1860. From there, it was issued to Captain Pray in support of his Virginia City militia unit.

Regardless of the story, the Nevada State Museum in Carson City is confident that not only was Frémont’s lost cannon found, but it resides safely among the Museum’s collection of artifacts. “We’re biased here,” said Gene Hattori, Ph.D., the Museum’s Curator of Anthropology. “We have Frémont’s Cannon in our possession.” Parts of a mountain howitzer carriage discovered a quarter century ago in the West Walker River Canyon along the California-Nevada border, are believed to be those from Frémont’s famous expeditionary cannon. The Frémont Howitzer Recovery Team came across two iron tire rims in an area where Frémont was thought to have abandoned the mobile artillery piece in 1844. “They believed that their finds were consistent with mountain howitzer carriage rims,” Dr. Hattori said, “but there were some uncertainties.”

Four years after the original find, another wheel rim, a trunnion plate and axle bracket assembly for an M-1835 Mountain Howitzer carriage were recovered from the same archaeological area—all but putting doubts to rest. “Key parts were similar, yet different than comparable parts from later versions of U.S. Mountain Howitzer carriages,” Dr. Hattori said. “This is almost certainly Frémont’s mountain howitzer carriage based on its discovery location and construction details.” He said the mountain howitzer tube in the Nevada State Museum’s collection is more than likely that of the famous Frémont Cannon.

Four years after the original find, another wheel rim, a trunnion plate and axle bracket assembly for an M-1835 Mountain Howitzer carriage were recovered from the same archaeological area—all but putting doubts to rest. “Key parts were similar, yet different than comparable parts from later versions of U.S. Mountain Howitzer carriages,” Dr. Hattori said. “This is almost certainly Frémont’s mountain howitzer carriage based on its discovery location and construction details.” He said the mountain howitzer tube in the Nevada State Museum’s collection is more than likely that of the famous Frémont Cannon.

According to research conducted by Col. Paul Rosen (retired), three mountain howitzers were requisitioned by the St. Louis Arsenal in 1837, and ours is one of six that were available to Frémont for his expedition. “The value of the mountain howitzer is its portability,” Dr. Hattori said, noting this feature would have appealed to Frémont, who had claimed he needed artillery for protection against hostile Native American attacks. Hattori said the Museum is confident that the artifact stamped with serial number three in its possession is the real deal, and that researchers like Rosen agree. “We’re at 75 to 90 percent certainty about the cannon tube and 99 percent certain on the carriage parts,” he said.

Frémont trailed the mounted cannon rather than disassemble and pack it the way that it was designed. “The carriage was intended to be towed only for short periods of time as it had a narrow wheelbase and wasn’t stable,” Dr. Hattori said.

Charles Preuss, the expedition’s cartographer, was less than fond of the artillery piece because it not only slowed down the expedition’s progress, but he also had to share the wagon with its ammunition! On January 29, 1844, Preuss, rather than Frémont, abandoned the cannon late in the day, intending to return for it later with Frémont.

Fearing starvation, they chose to find a Sierra pass leading to Sutter’s Fort instead.

And the rest, as they say, is history.